Պահակային ավշային հանգույցների բիոպսիա կրծքագեղձի վաղ փուլի քաղցկեղով հիվանդների մոտ.մեկ կենտրոնի փորձը Հայաստանից

Մետաքսյա Լ. Մկրտչյան1, Գագիկ Կ. Բազիկյան4, Արթուր Ա. Ավետիսյան1, Նարեկ Վ. Մանուկյան2, Մհեր Դ. Կոստանյան3, Զառա Ս. Հարությունյան5, Աննա Ա. Մելքոնյան5, Սաթինե Գ. Քարամյան5, Սուսաննա Գ. Ալեքսանյան5, Նելլի Հ. Գրիգորյան5, Սոնա Ա. Ջիլավյան6, Նաիրա Ռ. Հարությունյան8, Հայկուհի Կ. Գյոկչյան9, Ներսես Ս. Քարամյան10, Կարեն Հ. Ծառուկյան11, Անահիտ Վ. Գյունաշյան1, Խորեն Ե. Ամիրխանյան7

1 «Կանանց առողջության կլինիկա» բաժանմունք, Ֆանարջյանի անվան ուռուցքաբանության ազգային կենտրոն (ՈւԱԿ), Երևան, Հայաստան

2 Սերգեյ Սեինյանի անվան ոսկրային ուռուցքաբանության բաժանմունք, ՈւԱԿ, Երևան, Հայաստան

3 Ընդհանուր ու մանկական ուռուցքաբանության և ռեկոնստրուկտիվ վիրաբուժության բաժանմունք, ՈւԱԿ, Երևան, Հայաստան

4 Օնկոգինեկոլոգիական բաժանմունք 2, ՈւԱԿ, Երևան, Հայաստան

5 Կլինիկական պաթոմորֆոլոգիայի բաժանմունք, ՈւԱԿ, Երևան, Հայաստան

6 Ախտորոշիչ ծառայության բաժանմունք, ՈւԱԿ, Երևան, Հայաստան

7 Ուռուցքաբանության ամբիոն, Մ.Հերացու անվ. Երևանի պետական բժշկական համալսարան, Երևան, Հայաստան

8 Միջուկային բժշկության բաժանմունք, ՈւԱԿ, Երևան, Հայաստան

9 Քիմիոթերապիայի բաժանմունք, Էրեբունի բժշկական կենտրոն, Երևան, Հայաստան

10 Ճառագայթային թերապիայի բաժանմունք, ՈւԱԿ, Երևան, Հայաստան

11 Օնկոուրոլոգիայի բաժանմունք, ՈւԱԿ, Երևան, Հայաստան

ԱՄՓՈՓԱԳԻՐ

Ներածություն. Կրծքագեղձի քաղցկեղի (ԿՔ) վարման համատեքստում պահակային ավշային հանգույցների բիոպսիան (ՊԱՀԲ) հայտնի է դարձել որպես անութային ավշային հանգույցների հեռացման (ԱԱՀՀ) նվազագույն ինվազիվ այլընտրանքային մեթոդ: Վերջին տասնամյակների ընթացքում ԿՔ վիրաբուժական վարման պարադիգմն ականատես է եղել ագրեսիվ ընթացակարգերից ավելի պահպանողական մոտեցումների անցմանը: Այնուամենայնիվ, միջին եկամուտ ունեցող երկրներում ՊԱՀԲ-ի ներդրումը բախվում է բազմաբնույթ մարտահրավերների, ներառյալ սահմանափակ ռեսուրսները, վերապատրաստման բացերը և ֆինանսական սահմանափակումները:

Նպատակ. Սույն հետազոտության շրջանակներում ուսումնասիրվում է ՊԱՀԲ-ի ներդնումը միջինից բարձր

եկամուտ ունեցող երկրի՝ Հայաստանի Հանրապետության պետական հիվանդանոցում: Այն լույս է սփռում նորարարական վիրաբուժական տեխնիկայի ներդնման բարդ դինամիկայի վրա սահմանափակ ռեսուրսների պայմաններում:

Մեթոդներ. Այս հետահայաց-առաջահայաց ուսումնասիրությունը կենտրոնացած է այն հիվանդների շուրջ, որոնք 2020-ից 2022 թվականներին վիրաբուժական միջամտությունների են ենթարկվել վաղ փուլի ԿՔ-ի կապակցությամբ: Հետազոտվել է երկու խումբ. մի խումբը ենթարկվել է ՊԱՀԲ-ի՝ օգտագործելով ինդոցիանին կանաչ ներկանյութ և ռադիոիզոտոպ, մինչդեռ մյուս խումբը ենթարկվել է ԱԱՀՀ-ի:

Արդյունքները. Հետազոտությանը մասնակցել է

վաղ փուլի ԿՔ-ով 400 հիվանդ: Հիմնական բացահայտումներից են եղել ինվազիվ ծորանային քաղցկեղի, ER/PR-դրական, HER2-բացասական և տարբերակման 2-րդ աստիճանի ուռուցքների գերակշռությունը: Հիվանդների մեծ մասը (95.3%) ստացել է ճառագայթաբուժություն և հորմոնաբուժություն (85.3%)՝ առանց ՊԱՀԲ և ԱԱՀՀ խմբերի միջև տարբերությունների, մինչդեռ քիմիաբուժությունն ավելի հաճախ եղել է ԱԱՀՀ խմբում (79.7% ընդդեմ 22.8%, P < 0.001):

Եզրակացություն. ՊԱՀԲ-ի ներդնումը միջինից բարձր եկամուտ ունեցող երկրում բախվում է մարտահրավերների՝ կապված ռեսուրսների, ուսուցման և ֆինանսական սահմանափակումների հետ: Չնայած այս խոչընդոտներին, վիրահատական բուժման նորարարական ռազմավարությունները, ինչպիսիք են ինդոցիանին կանաչ ներկանյութի և ռադիոիզոտոպի կիրառմամբ ՊԱՀԲ-ն, առաջարկում են

հնարավոր լուծումներ: Շրջանցելով այս խոչընդոտները՝ ՊԱՀԲ-ի ինտեգրումը կարող է բարելավել ԿՔ

բուժման կազմակերպումը և բուժական ելքերը սահմանափակ ռեսուրսների պայմաններում:

Հիմնաբառեր. ավշային հանգույցների բիոպսիա, կրծքագեղձի քաղցկեղ, միջինից բարձր եկամուտ ունեցող երկիր, վիրաբուժական նորարարություն, ռեսուրսների սահմանափակումներ, ինդոցիանին կանաչ, նվազագույն ինվազիվ, ախտորոշման ճշգրտություն

DOI: 10.54235/27382737-2024.v4.1-13

TRODUCTION

In 2008, the diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) presented a dichotomy on a global scale. High-resource countries recorded around 636,000 new cases, whereas their low- and middle-resource counterparts reported 514,000 cases, establishing BC as the predominant cancer among women in the latter group. The global incidence rates of BC exhibited a wide spectrum, spanning from 19.3 cases per 100,000 women each year in Eastern Africa to a considerably higher 89.9 cases per 100,000 women yearly in Western Europe [1]. These statistics foreshadowed a significant shift in the BC landscape, predicting that by 2020, a substantial 70% of all BC cases worldwide would emerge in low- and middle-resource countries [2]. This transition was attributed to multifaceted factors, including increased life expectancy, decreased mortality from infectious diseases, and evolving reproductive and lifestyle choices.

One prevailing misconception in low-resource countries (LRCs) was the perception that BC predominantly affected younger age groups due to lower life expectancies. However, research refuted this notion. Studies by Akarolo-Anthony et al. (2010) for Africa [3], Autier et al. (2010) for European countries [4], and global reports indicated that BC rates among young women in LRCs were not higher than those in developed nations [4-6]. In fact, BC incidence among young women was more related to life expectancy. Countries with a life expectancy of less than 60 years exhibited lower BC incidence due to fewer women reaching an age at which BC typically manifests. In contrast, as life expectancy increased, so did the incidence of BC [5,7]. Economic development and changing lifestyles further shaped BC patterns in LRCs. Shifts toward having fewer children, delayed first pregnancies, and shorter breastfeeding durations contributed to heightened BC risk. Consequently, LRCs experienced a surge in BC incidence rates.

However, the challenges extended beyond incidence rates to survival rates, unveiling stark differences between low- and high-resource countries. The five-year survival rates for BC were alarmingly low in low-income African countries, such as The Gambia, where rates remained at a mere 19% [8]. In contrast, North America boasted survival rates exceeding 80%. Several factors contributed to these divergent survival rates, including the absence of early detection programs, late-stage disease presentations, insufficient diagnostic and treatment facilities, and limited access to professional medical care in low-resource settings [9]. This stark contrast in survival rates underscored the urgent need for comprehensive interventions to enhance BC care and outcomes in LRCs.

What stage of breast cancer is commonly

identified at the time of diagnosis in LRCs?

In LRCs, BC often reaches an advanced stage at the time of diagnosis due to the absence of organized screening programs. The prevailing pattern involves the classic discovery of a “painless breast lump” by the affected individuals themselves. Regrettably, women in these regions tend to live with this symptom for prolonged periods, sometimes spanning months or even years, before seeking medical attention. It is not uncommon for complications like pain, ulcers, foul-smelling purulent discharge, or signs of metastatic disease to prompt them to seek medical help [7,12-15].

During this delay, women might suspect the change in their breast to be cancer-related but might hesitate to seek a diagnosis, often due to the fear associated with cancer and its treatments [15]. Instead, they might opt to consult alternative healthcare providers, further prolonging the time before consulting a medical professional. Consequently, many cases of BC in LRCs are identified only when the disease has already progressed significantly.

However, there is a ray of hope. Demonstrative initiatives have indicated that heightened awareness about breast health within communities can lead to the detection of BC at an earlier stage. This includes identifying smaller-sized tumors with minimal or no spread. In these regions, clinical breast examination (CBE) emerges as the primary method for early detection. CBE, which can be seamlessly integrated into routine clinical evaluations for various medical concerns, obviates the immediate need for image-guided sampling. Yet, if feasible, diagnostic imaging can offer valuable insights into disease extent and assist in precise needle targeting for tissue sampling [16]. In essence, the absence of systematic screening programs in LRCs often results in BC being identified at an advanced stage, primarily due to the self-detection of painless breast lumps. Overcoming this challenge necessitates empowering communities with breast health awareness and facilitating clinical breast examinations. While CBE remains a pivotal tool for early detection, leveraging available diagnostic imaging resources can further enhance diagnostic accuracy and comprehensive disease evaluation [17].

What are the pathology service

requirements in LRCs?

In LRCs, the provision of adequate pathology services is crucial for effective healthcare delivery, especially in the context of diseases like cancer. However, due to various challenges, these countries often face specific requirements to ensure efficient and reliable pathology services. Pathology services in LRCs require basic infrastructure such as well-equipped laboratories, proper storage facilities for samples, and reliable energy sources. Access to functioning microscopes, centrifuges, staining equipment, and tissue processing machines is essential for accurate diagnosis [18]. A shortage of skilled pathologists, histotechnologists, and laboratory technicians is a common issue in LRCs. It is vital to provide training and continuous education for these professionals to ensure accurate specimen handling, processing, and interpretation [19]. Establishing quality assurance programs is crucial to maintain accurate results. Regular external quality assessments, proficiency testing, and adherence to international standards help prevent errors and ensure the reliability of pathology reports. Efficient systems for proper specimen collection, labeling, and transportation are essential to prevent degradation and ensure accurate analysis. Lack of proper transportation can lead to delays and compromised results.

Cost-effective diagnostic tests are necessary to make pathology services accessible to the population. Efforts to negotiate favorable pricing for reagents, equipment, and supplies can contribute to sustainability.

In conclusion, establishing effective pathology services in LRCs requires a comprehensive approach addressing infrastructure, trained personnel, quality assurance, diagnostics, data management, and affordability. By focusing on these requirements, LRCs can improve their healthcare systems and provide accurate diagnoses crucial for patient care and disease management.

How is tissue sampling

performed in LRCs?

Within low-resource settings, the task of achieving accurate pathological diagnoses necessitates the utilization of available tissue sampling techniques. In this context, two prominent procedures come to the forefront: fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and core needle biopsy [20].

In resource-limited environments, FNAC emerges as a straightforward, budget-conscious, swift, and easily repeatable method. This technique proves particularly valuable when dealing with clinically palpable tumors. However, it requires expertise in cytopathology, and the availability of certified cytopathologists remains limited in such regions [21,22]. The occasional performance of FNAC can yield suboptimal results [23].

On the other hand, core needle sampling showcases potentially superior diagnostic sensitivity and specificity compared to FNAC [24,25]. This method yields more substantial tissue samples, facilitating histological diagnosis and hormone receptor (HR) analysis. However, it demands comparatively expensive equipment, generally lacks immediate interpretive capability, and mandates the involvement of an adept pathologist. While experts advise the preference of FNAC or core biopsy over surgical excision whenever feasible, the practice of surgical biopsy (excisional or incisional) remains prevalent in low-resource settings [26]. Effective diagnosis and treatment hinge on proper tissue handling, appropriate specimen transportation, and accurate fixation and staining procedures. In the absence of these essential components within low-resource settings, the challenges of achieving accurate diagnoses and effectively characterizing breast tumors, both at an individual and population level, become pronounced. These limitations impact not only individual patient care but also hinder comprehensive breast tumor studies within the population [27,28].

How is quality control for pathology

managed in LRCs?

Quality control and assurance for pathology services in LRCs face significant challenges, often resulting in suboptimal outcomes [29]. A lack of well-established protocols for the preparation and fixation of tissue samples can lead to hindered utilization of advanced techniques like immunohistochemistry and molecular biology. As a consequence, the reliability and consistency of results are compromised, contributing to misinformation and inflated rates of HR-negative cancers [27,28].

Interestingly, the assessment of HR status from needle biopsies demonstrates greater reliability when compared to mastectomy specimens derived from the same patients. Notably, this phenomenon has been observed in distinct studies conducted in different regions, such as the Philippines and Australia. This discrepancy might be attributed to the expedient processing of smaller needle biopsy samples, which are promptly immersed in fixatives and exhibit improved fixative penetration due to their reduced size [30,31].

In essence, the existing challenges in quality control and assurance for pathology services in LRCs underscore the need for enhanced protocols and training to ensure accurate and dependable results, especially in the realm of advanced pathological techniques. Addressing these issues can significantly contribute to more reliable diagnostic outcomes and ultimately improved patient care.

PURPOSE

The purpose of this study is to investigate the adoption and implementation of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) in the management of early-stage breast cancer (EBC) within a public hospital in an upper middle-income country. By examining the outcomes of patients who underwent SLNB using indocyanine green and gamma probe detector in comparison to those who underwent the more traditional axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), the study seeks to evaluate the efficacy and potential benefits of SLNB in optimizing BC care delivery and improving patient outcomes in such settings.

METHODS

This was a single-center retrospective and prospective study that included all BC patients who had SLNB or ALND at the National Oncology Center in Yerevan, Armenia, between 2020 and 2022. For patients with node-negative EBC, SLNB was performed primarily as an upfront procedure and, in rare instances, after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT). All cT1-3N0 BC patients received SLNB in accordance with institutional practice. Patients with locally advanced and recurrent BC were not given access to SLNB. Before recommending SLNB, clinically node-negative patients who had suspicious axillary nodes identified by axilla ultrasound underwent FNAC to validate the node-negative status. Patients with BC and FNAC-proven node positivity underwent ALND. All patients with invasive BC, tumor size of 5 cm or smaller (T1/T2), and imaging-confirmed clinically node-negative axilla were included. Exclusion criteria were: age older than 75 years, previous NACT or previous surgery to the breast or axilla, diagnosis multicentric cancer or inflammatory breast malignancy.

SLNB is now done using the vital stain method, the radionuclide method, or the combination method. In general, the radionuclide method has a better level of accuracy than the vital stain method. Despite its excellent accuracy, this method necessitates the use of professional equipment and reagents, and the SLNB procedure is quite difficult. The strong concern about radioactivity also restricts its clinical application. The crucial stain process is inexpensive and simple to employ. Total mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery was chosen for the primary tumor based on patient preference and tumor characteristics. A total of 5 mL of dye (methylene blue, indocyanine green [ICG], or technetium-99) was injected into the periareolar/intradermal site. Before the skin incision, manual pressure and gentle massage were applied to the injection site for 5 minutes. All blue lymph nodes were harvested and sent for frozen sectioning (FS) intraoperatively. Indications for completing ALND in certain situations were: (1) the SLN was positive for tumor cells on FS, and (2) the SLN could not be identified. All SLNs were serially sectioned at 1 mm intervals, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin according to laboratory protocols.

The quality of life (QOL) of the patients was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast plus Arm Morbidity (FACT-B+4) questionnaire. It is used to measure the QOL in BC patients, particularly those who experience lymphedema. The FACT-B+4 includes 41 items distributed across 6 domains: Physical Well-Being (PWB), Social/Family Well-Being (SWB), Emotional Well-Being (EWB), Functional Well-Being (FWB), Breast Cancer Subscale (BCS), and Lymphedema Subscale. It uses a 5-point Likert scale and typically takes 10-15 minutes to complete, either through self-administration or an interview. The main focus of the survey was the Trial Outcome Index (TOI) score, which is the sum of PWB, FWB and BCS domains of the FACT-B+4 [32]. A non-validated Armenian translation of the FACT-B+4 was used for this study.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Center of Oncology, and all participants provided written informed consent.

RESULTS

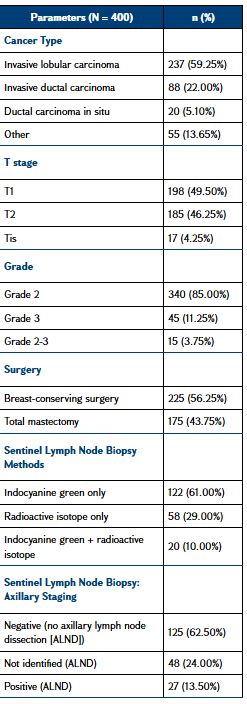

During the 3-year period from January 2020 to December 2022, a total of 445 patients underwent SLNB and/or ALND for EBC (<3 cm) and no palpable axillary nodes. Twelve patients were excluded because of previous NACT, five because of severe shoulder pain and limitation before surgery. Twenty participants refused to complete the quality-of-life (QOL) questionnaires at baseline, and another eight refused to continue in the study after baseline evaluation (five SLNB and three ALND). Therefore, 400 female patients were included in the study with a mean (± standard deviation) age at diagnosis of 55.8 ± 12.8 years [range: 30-81 years]; the majority were post-menopausal (79.3%). The education level and the work status did not show significant differences between groups.

Out of the 400 included patients, 145 underwent SLNB, 55 SLNB followed by ALND, and 200 ALND as the first procedure. Patients were randomized to either blue dye alone or combined mapping for SLNB. All the 200 women of the SLNB group had a level I and II ALND after the SLNB. Baseline differences in tumor size category, node involvement, metastasis (TNM) cancer staging were statistically significant: the SLNB group was mostly composed of patients in T1 or carcinoma in situ (87.1%) and N0, while almost half the patients presented T2 and 75.4% N ≥ 1 in the ALND group. The majority of BCs were invasive lobular carcinoma (59.25%) or invasive ductal carcinoma (22%), grade 2 (85.00%), grade 3 (11.25%) or grade 2-3 (3.75%). The upper outer quadrant of the breast was the location of 60% of malignancies in 50.7% of cases: multicentric BCs affected 14.9% of the patients. The mean (± standard deviation) number of lymph nodes removed in the ALND group was 17.9 ± 6.4. Most patients received radiotherapy (95.3%) and hormonotherapy (85.3%) without differences between SLNB and ALND groups, while chemotherapy was significantly more frequent in the ALND group (79.7% vs. 22.8%; P < 0.001). Baseline clinical characteristics of the study cohort are summarized in Table 1.

QOL questionnaire completion rates at follow-up were 95.7%, 90.3%, and 86.0% at 1, 6, and 12 months after surgery, respectively. The impact of surgery on the Arm Morbidity Scale of the FACT-B+4 questionnaire was higher among patients who underwent ALND, with the mean scores presenting statistically significant differences between groups at 1, 6, and 12 months after surgery. Surgery impact on TOI score was higher in the short term, especially for the ALND group. Both groups showed a similar pattern of initial deterioration and subsequent recovery on FACT-B+4 questionnaire.

DISCUSSION

Sentinel lymph node biopsy is a well-established procedure in many parts of the world, including Armenia, for the staging and management of certain cancers, particularly BC and melanoma. SLNB was carried out in accordance with the institutional protocols, with the unique dye combinations depending on the radioactive dye availability. Methylene blue dye was used between 2020 and 2022 whenever Tc-99 was unavailable. Since July 2020, ICG-based SLNB has been also implemented to address the unavailability of radioactive isotopes. Tc-99 injection and gamma probe (EuroProbe3) had been used to localize the new nodes. 2 mL of 1% methylene blue dye was used for blue dye SLNB. Injection of 1 mL (2.5 mg) of ICG and an infra-crimson digicam (Irillic.nm System) have been utilized to perceive the fluorescent nodes. The nodes with most radioactivity or visibly blue-stained, fluorescent and clinically suspicious nodes had been considered SLNs. The SLNs have been dispatched for FS exam.

As expected, SLNB performed better than ALND in terms of QOL. The studies comparing SLNB and ALND found that patients in the ALND group reported significantly worse physical and functional well-being shortly after surgery compared to those in the SLNB group [33]. The differences in TOI scores revealed by us highlight the less invasive nature of SLNB and its role in enhancing the QOL for patients in the immediate postoperative period.

With the fourth highest BC mortality rate in the world, BC prevention and early detection is a priority for Armenia, an upper-middle income country in the South Caucasus. The Ministry of Health recently initiated efforts to expand access to BC screening. Armenia has been steadfastly advancing its healthcare system to meet the evolving needs of its population. BC is an important cause of mortality among adult women in Armenia. Statistics are particularly concerning among Armenian women ages 15–49: in this age group, BC proportionally causes nearly three times as many deaths as worldwide (14% vs. 5% of deaths), with a mortality-to-incidence ratio of nearly 50% [10,11].

SLNB is a critical procedure in modern oncology, particularly for staging cancers such as BC and melanoma. This technique offers several advantages over traditional methods like ALND, making it a preferred choice for both patients and healthcare providers. SLNB is a valuable tool in cancer management, offering accurate staging, reduced complications, and quicker recovery. Its minimally invasive nature and cost-effectiveness make it a superior option, significantly benefiting patients both in the short and long term. Many centers using SLNB, no longer perform ALND for histologically negative axillary SLNs. Moreover, SLNB may have also a therapeutic role because in most patients, the SLN is the only positive axillary node [34].

CONCLUSION

Sentinel lymph node biopsy is a more sensitive and accurate technique for nodal evaluation and staging of axillary lymph nodes in patients with BC, providing prognostic information, with less surgical morbidity than with ALND. The study highlights the challenges and barriers faced in introducing SLNB in a resource-constrained environment, focusing on aspects such as resource limitations, training deficits, and financial constraints.

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893-917

Garcia M, Jemal A, Ward EM, Center MM, Hao Y, Siegel RL, Thun MJ. Global Cancer Facts & Figures 2007. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, 2007

Akarolo-Anthony SN, Ogundiran TO, Adebamowo CA. Emerging breast cancer epidemic: evidence from Africa. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(S4):S8

Autier P, Boniol M, La Vecchia C et al. Disparities in breast cancer mortality trends between 30 European countries: retrospective trend analysis of WHO mortality database [published correction appears in BMJ. 2010;341:c4480. LaVecchia, Carlo [corrected to La Vecchia, Carlo].]. BMJ. 2010;341:c3620

Parkin DM, Fernández LM. Use of statistics to assess the global burden of breast cancer. Breast J. 2006;12(S1):S70-S80

Coleman MP, Quaresma M, Berrino F et al. Cancer survival in five continents: a worldwide population-based study (CONCORD). Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(8):730-756

Adebamowo CA, Ajayi OO. Breast cancer in Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2000;19(3):179-91

Bray F, McCarron P, Parkin DM. The changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(6):229-39

Curado MP, Edwards B, Shin HR et al. Cancer incidence in five continents, Volume IX. IARC Press, International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2007

Sankaranarayanan R, Swaminathan R, Brenner H et al. Cancer survival in Africa, Asia, and Central America: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):165-173

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD compare. In: Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington [Internet]. 2015

Ryzhov A, Corbex M, Piñeros M et al. Comparison of breast cancer and cervical cancer stage distributions in ten newly independent states of the former Soviet Union: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(3):361-9

Anyanwu SN. Temporal trends in breast cancer presentation in the third world. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27(1):17

El Saghir NS, Khalil MK, Eid T et al. Trends in epidemiology and management of breast cancer in developing Arab countries: a literature and registry analysis. Int J Surg. 2007;5(4):225-33

Chopra R. The Indian scene. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(S18):106-11S

Ajekigbe AT. Fear of mastectomy: the most common factor responsible for late presentation of carcinoma of the breast in Nigeria. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1991;3(2):78-80

Clegg-Lamptey J, Hodasi W. A study of breast cancer in korle bu teaching hospital: assessing the impact of health education. Ghana Med J. 2007;41(2):72-7

Kerlikowske K, Smith-Bindman R, Ljung BM, Grady D. Evaluation of abnormal mammography results and palpable breast abnormalities. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(4):274-84

Anderson BO, Jakesz R. Breast cancer issues in developing countries: an overview of the Breast Health Global Initiative. World J Surg. 2008;32(12):2578-85

Masood S, Vass L, Ibarra JA Jr et al. Breast pathology guideline implementation in low- and middle-income countries. Cancer. 2008;113(S8):2297-304

Shyyan R, Sener SF, Anderson BO et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: diagnosis resource allocation. Cancer. 2008;113(S8):2257-68

Vargas HI, Masood S. Implementation of a minimally invasive breast biopsy program in countries with limited resources. Breast J. 2003;9(S2):S81-5

Ljung BM, Drejet A, Chiampi N et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration biopsy is determined by physician training in sampling technique. Cancer. 2001;93(4):263-8

Wu YP, Cai PQ, Zhang WZ et al. [Clinical evaluation of three methods of fine-needle aspiration, large-core needle biopsy and frozen section biopsy with focus staining for non-palpable breast disease] Ai Zheng. 2004;23(3):346-9

Agarwal T, Patel B, Rajan P, Cunningham DA, Darzi A, Hadjiminas DJ. Core biopsy versus FNAC for palpable breast cancers. Is image guidance necessary? Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(1):52-6

Bevers TB, Anderson BO, Bonaccio E et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer screening and diagnosis [published correction appears in J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010 Feb;8(2):xxxvii. Buys, Sandra [corrected to Buys, Saundra]; Yaneeklov, Thomas [corrected to Yankeelov, Thomas]]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(10):1060-1096

Shet T, Agrawal A, Nadkarni M et al. Hormone receptors over the last 8 years in a cancer referral center in India: what was and what is? Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52(2):171-4

Adebamowo CA, Famooto A, Ogundiran TO et al. Immunohistochemical and molecular subtypes of breast cancer in Nigeria. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110(1):183-8

Togo A, Traore A, Traore C et al. Breast cancer in two hospitals in Bamako (Mali): diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. J Afr Cancer. 2010;2(2):88-91

Howat A. Report by Alec Howat for BDIAP Council on Support for sub-Saharan Anglophone African Pathology. Journal [serial on the Internet]. Available from: http://www.bdiap.org; 2008

Mann GB, Fahey VD, Feleppa F, Buchanan MR. Reliance on hormone receptor assays of surgical specimens may compromise outcome in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5148-54

Coster S, Poole K, Fallowfield LJ. The validation of a quality of life scale to assess the impact of arm morbidity in breast cancer patients post-operatively. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;68(3):273-82

Che Bakri NA, Kwasnicki RM, Khan N, et al. Impact of axillary lymph node dissection and sentinel lymph node biopsy on upper limb morbidity in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2023;277(4):572-80

Amersi F, Hansen NM. The benefits and limitations of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2006;7(2):141-51