tion

Among all malignant tumors in 2020 cervical cancer (CC) ranked 7-th in the world, 4-th — among neoplasms in women, 2-nd — in frequency among malignant tumors of the reproductive system in women and first among the causes of female cancer deaths in developing countries. In addition, cervical cancer ranks fourth among the most commonly diagnosed tumors and is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in women [1].

Early detection through screening and treatment of precancerous cervical cancer lesions (PCCL) remains the best possible protection against cervical cancer, with 75% incidence reduction in developing countries [2]. Multiple reasons, including low level of knowledge, high cost, non-proper availability of screening services, and other factors (such as perceptions, poor attitude, and distance), are revealed in the literature presenting the CC screening uptake analysis [3] .

In the previous 5 years, the number of cervical cancer deaths has fluctuated between 300,000 and 350,000. About 85% of cervical cancer deaths worldwide occur in low- and middle-income countries. In these countries, mortality is 18 times higher than in developed countries.

Prevention measures were effective and contributed to cervical cancer decline in a large number of countries. The World Health Organization in 2020, (WHO) indicated a target of 70% CC screening coverage for women aged 35–45 years in 2030 [4].

One of the few malignancies for which primary prevention (vaccine) and screening using diverse techniques (HPV test, Pap test) have been successfully implemented in many nations is cervical cancer [4].

According to a recent modeling study conducted in 181 countries, HPV vaccination and the widespread adoption of cervical cancer screening strategies could prevent between 12.5 million and 13.4 million new cases of cervical cancer from 2020 to 2070, and by the end of the century, the disease could be nearly completely eradicated in most countries [5].

It should be mentioned that both developed and developing nations have obstacles when it comes to cervical cancer screening. Moreover, several obstacles are the same or comparable in both groups of nations. According to a survey conducted in 18,000 women in the UK between the ages of 25 and 64, the most common reasons given for not getting screened for cervical cancer were time constraints, embarrassment or discomfort from the screening process, and pain caused by the treatment itself [6].

According to a survey involving immigrant women in Canada, the most frequent obstacles to the screening procedure were the lack of efficient doctor-patient communication, the sense of discomfort when male doctors were participating in the process, and a lack of public awareness of health issues [7].

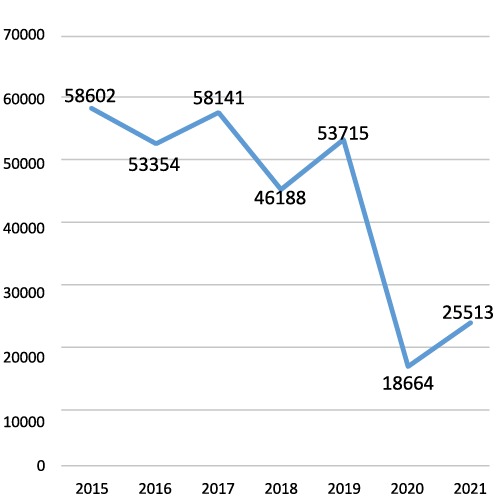

In 2015 year, Armenia launched a National screening program for women aged 30–60 years aimed to decrease cervical cancer morbidity and mortality. It set a goal that screening coverage should reach 50% in women aged 30–60 years by 2021. However, 328,881 people were involved in the program, which was 21% of women in Armenia for the specified period, and less than 45% of the age-standardized (targeted) population. The governmental data sources were used to estimate the screening coverage in Armenia within 2015-2021 (period of National screening Program implementation) [9].

The total and annual uptake of the organized screening in 2015-2021 is presented in the Fig.1. As shown in the figure the annual uptake of organized screening was between 18 664 and 53 725 in the period of 2015-2021. The peak of cohort engagement was observed in 2015 and the most essential critical decline in the year 2020. The total number of participants was 328 881 which was about 21% of female population in Armenia and less than 45% of age-adjusted (targeted) female population.

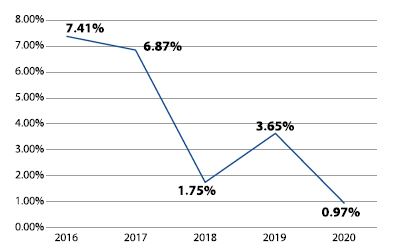

The graph in Fig.2 shows the maximum percentage of the revealed cases in the period of 2015-2017 (around 6%) with the essential nadir in 2019 year (2.5%).

This study aimed to verify and analyze the barriers and obstacles influencing individuals’ decision to participate in a prospective screening program.

Material and methods

Data collection

Overall 328 881 patients were investigated between January 2015 and December 2021 via Pap-test in the scope of National Screening Program [8].

Data retrieved from the official sources and used for the retrospective study included proportion of the Armenian female population constituting the size of the cohort screened in the specified timeframe of the program.

This descriptive study was carried out between August and October of 2023 in a representative sample of 30-60 years old Armenian women never screened for CC and applied to WWC MOH RA within the mentioned timeframe.

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in the approval by human research committee. All participants were informed about the study’s content and purpose, and gave written informed consent to participate in the trial and to use their data.

The sample cohort of the study included 482 Armenian females. Stratified random sampling was used to select participants from WWC patients. The determined representative sample included 601 women aged 30-60 years. Based on the selection criteria 119 individuals were excluded due to being screened previously and only 482 females took part in the survey. The age frame was selected to ensure the validity of the information received from respondents in terms of the adequacy of its assessment and further comparability of other study cohorts.

The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows:

- Armenian citizenship

- 30–60 years age,

- No current or prior diagnosis of cervical cancer or other cervical anomalies.

- Never being screened for CC

Exclusion criteria:

- Language barrier

- Mental disorders

- Refusal to be included in the study

Obtained information from the prospective study included: data generated by using structured interview with self-administered questionnaire (adopted from similar studies and translated into Armenian) [9-12].

The evaluation was addressing several key points: the goals of measurement, the target population, analysis of concepts (important aspects) targeted by the measurement, selection of questions, as well as concision or relevancy. The average time to complete the questionnaire was approximately 10 to 15 min.

The adopted questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part was to verify the social-demographic characteristics of respondents (eleven criteria, including age, education level, area of residency, employment status, marital status and number of children in the family, health insurance coverage, self-estimated health status, family history of CC) (Supplement 1). The second part aimed to reveal the participant’s relation and kind of barriers to CC screening program. Knowledge questions were designed to be answered with “Yes”, “No” or “Don’t know” (Supplement 2). Total amount of questions in both domains was 42 questions.

A questionnaire designed by an expert group including screening program staff, psychologists, oncologists and practicing gynecologists. Preliminary testing was conducted in 28 respondents for the validation purpose.

The questions were divided into 3 groups (releted to the barriers): related to psychological factors, knowledge related and doctors related.

The questions revealing psychological barriers included the factors regarding the respondents’ attitude to the importance of screening, attitude to the importance of the respondents’ health, fear of procedure, fear of positive result, fear of interspousal relationship dissolution, non willingness to attend a medical facility, procrastination factors etc.

The knowledge related questions were focused on cervical cancer screening procedure and screening efficacy, such as CC preventive measure, screening facilities, procedure, its technique and duration.

Questions related to doctors included questions regarding respondents’ attitude toward the healthcare system, accuracy of the tests, reliability of information storing depending on the skills and personality of their doctors.

A “yes” score resulted in 1 point and 0 point was given for the other responses. The total sum of points increasing the 50% of the maximum possible score value in each group was estimated as a positive result or a barrier.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 23.0 (SPSS®): Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The frequencies and percentages were calculated. Questions related to factors’ measure were calculated by adding the answers regarding the concrete type of the barrier to screening, then dividing them by the overall number of questions related to the parameter of interest to be measured and multiplying the number by 100%. Comparisons between socio-demographic data and barriers to screening were measured using the Chi-square test. The chosen level of significance was at 0.05.

Results

The data presenting social — demographic characteristics of respondents as well as the relationship between types of barriers to screening and the social — demographic characteristics is shown in Fig.3.

Out of 482 total respondents, the majority 183 (40.7 %) was in the age range 30–39, the mean age was 34.8 (± SD 3.21), and the minimum and maximum age in total cohort was 30 and 59 respectively. The main part of the participants 294 (61.8%) were married. Part of the participating females 188 (38.2 %) were from urban area and 294 (61.8%) — had rural residence. 256 (53.1 %) of the respondents held a university diploma or scientific degree, while only 31 (6.4%) had secondary education. 196 (40.66%) respondents were housewives. One hundred and eighty nine (39.21%) respondents were insured. The Family history of CC was defined as positive in 61 (34.08%) cases while 39 (30%) did not present appropriate information Fig.3.

Relationship between social — demographic variables and kind of barriers to Screening

Comparison of demographic characteristics of participants (age, education, residence area, number of children, employment and insurance statement and income level) and kinds of barriers to Screening of cervical cancer rejected the null hypothesis with a very high probability. The comparative analysis demonstrated strong evidence of dependence between some of the variables: educational level, residence area, being or non-being insured, family history of CC and kinds of barriers to CC Screening. As anticipated, there was no association between the age and marital status data categories with kind of barriers to Screening (Df=4, χ2 value=0.0175, p=.999 and Df=6, χ2 value= 0.9081, p=0.999 correspondingly for age and marital status) as well as between the Health Status (by self-estimation) and barrier type (Df=4, χ2 value= 0.086, p=.99). No significant association was also observed between number of children (Df=2, χ2 value=0.0145, p=.992) and employment status (Df=4, χ2 value=0.0924, p=.998 ) data with kind of barriers to Screening.

This is enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis due to χ2 value exaggeration over the critical value and p-value <.05 in some of categories of variable. So, the strong association was revealed between educational level and type of barriers to screening of CC (Df=6, χ2 value= 14.493) as well as between being or non-being insured and barriers (Df=2, χ2 value= 7.53 ). Another strong relationship with kind of barrier was shown in data categories regarding residence area ( Df=2, χ2 value = 7.59). The data regarding family history of cervical cancer also demonstrated interconnection evidence (Df=4, χ2 value=8.248).

The data obtained also allows us to conclude about the dominant association of knowledge-related and doctor-related barriers with rural residence (106 vs the expected 100 and 106 vs the expected 98 correspondingly for knowledge-related and doctors-related barriers) while the urban residents mentioned mainly psychological barriers (75 vs the expected 62). The knowledge related barriers were mostly revealed by respondents with unclear CC Family history (59 vs the expected 44), and University diploma holders (100 vs the expected 85). The insured respondents (76 while the 63 expected) mentioned the doctor related barrier while psychological barriers were mostly revealed in non-insured patients (106 vs the expected 95). The differences were statistically significant (p=.023, p=.025, p=.023 and p=.00867 respectively for residence area, education level, insurance status and family history of CC), suggesting the high likelihood of refusal to screening participation due to revealed barriers.

Discussion

The factual coverage of the target population by the CC screening program was significantly lower than the predefined target rate. This low rate has necessitated a study to analyze the reasons for low screening uptake in Armenia.

This study was carried out to assess the underlying obstacles of CC screening program, leading to the low uptake. The current study revealed 157 (32.57%) respondents who mentioned psychological barriers, 164 (34.02%) did not possess sufficient knowledge regarding CC screening and 161(33.40%) participants were not enough trustful to the medical staff.

Women with higher education are more likely (39.06%) to have barriers or concerns regarding the professionalism of doctors, whereas for the respondents without higher education, factors restraining them from participation were psychological (13 (41.94%) & 59 (34.91%) — respectively for respondents, graduated from Secondary school and having vocational education).

34.02% of the survey respondents demonstrated the knowledge- related and 33.40% doctor-related types of barriers to screening. The psychological kind of barriers were registered in 32.57% of survey participants.

The most significant lack of CC screening knowledge was observed in categories of respondents with low awareness of CC family history (45.38%) and rural area inhabitants (36.05%). The most expressed deficiency of trust toward Doctors, Facilities and Health Care system was revealed in insured respondents and university graduates.

Other than high prevalence of cervical cancer and low screening uptake, as factors influencing the participation in Screening program, the knowledge related to reasons for non-involvement in programs is of not minor importance for the health care system. The reported high rates of knowledge and doctor related barriers to Screening Program compose a serious alarming evidence. It has the strength to generate significant obstacle on the way to WHO indicated target of 70% screening coverage as a CC elimination measure in developing countries [13-17].

CONCLUSION

The conducted study demonstrated the poor uptake of screening program in 2015-2021 as well as the significant rate of knowledge related barriers to screening as a prevention method of CC. Strong interconnection exists between barriers to screening and residence area and between barriers to screening and family history of CC, insurance and level of education. The second registered barrier was the group of factors related to doctors. The obtained data stipulate enhancement of the measures of health care staff education both regarding CC preventability and screening efficacy as a pre-cancer important diagnostic measures with anticipation of the further sharing of the received data with the patients population.

The short period of the survey and a fast track of data analysis with country-level independent variables has revealed the country specific current rates for the assessed variables.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021. Vol. 71, N 3. P. 209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

- 2. Seyoum T, Yesuf A, Kejela G, Gebremeskel F. Utilization of cervical cancer screening and associated factors among female health Workers in Governmental Health Institution of Arba Minch town and Zuria District, Gamo Gofa zone, Arba Minch, Ethiopia, 2016. Arch Cancer Res. 2017].

- 3. Bayu H, Berhe Y, Mulat A, Alemu A. Cervical cancer screening service uptake and associated factors among age eligible women in Mekelle zone, Northern Ethiopia, 2015: a community based study using health belief model. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149908.

- 4.World Health Organization. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107. [2022-6-28].

- Simms KT, Steinberg J, Caruana M, Smith MA, Lew JB, Soerjomataram I, et al. Impact of scaled up human papillomavirus vaccination and cervical screening and the potential for global elimination of cervical cancer in 181 countries, 2020-99: a modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Mar;20(3):394-407.

- Wilding S, Wighton S, Halligan D, West R, Conner M, O’Connor DB. What factors are most influential in increasing cervical cancer screening attendance? An online study of UK-based women. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2020 Aug 7;8(1):314-28).

- Ferdous M, Lee S, Goopy S, Yang H, Rumana N, Abedin T, et al. Barriers to cervical cancer screening faced by immigrant women in Canada: a systematic scoping review. BMC Womens Health. 2018 Oct 11;18(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0654-5.)

- https://healthpiu.am/%d5%bd%d6%84%d6%80%d5%ab%d5%b6%d5%ab%d5%b6%d5%a3%d5%b6%d5%a5%d6%80/).

- Tadesse F, Megerso A, Mohammed E, Nigatu D, Bayana E. Cervical Cancer Screening Practice Among Women: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study Design. Inquiry. 2023 Jan-Dec;60:469580231159743. doi: 10.1177/00469580231159743.

- Weng, Q., Jiang, J., Haji, F.M. et al. Women’s knowledge of and attitudes toward cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening in Zanzibar, Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer 20, 63 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-6528-x

- Tekle T, Wolka E, Nega B, Kumma WP, Koyira MM. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards Cervical Cancer Screening Among Women and Associated Factors in Hospitals of Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Cancer Manag Res. 2020 Feb 11;12:993-1005. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S240364. PMID: 32104081; PMCID: PMC7023884.

- Lemp JM, De Neve JW, Bussmann H, Chen S, Manne-Goehler J, Theilmann M, Marcus ME, Ebert C, Probst C, Tsabedze-Sibanyoni L, Sturua L, Kibachio JM, Moghaddam SS, Martins JS, Houinato D, Houehanou C, Gurung MS, Gathecha G, Farzadfar F, Dryden-Peterson S, Davies JI, Atun R, Vollmer S, Bärnighausen T, Geldsetzer P. Lifetime Prevalence of Cervical Cancer Screening in 55 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA. 2020 Oct 20;324(15):1532-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16244].

- Mukosha M, Muyunda D, Mudenda S, Lubeya MK, Kumwenda A, Mwangu LM, Kaonga P. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards cervical cancer screening among women living with human immunodeficiency virus: Implication for prevention strategy uptake. Nurs Open. 2023 Apr;10(4):2132-2141. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1460. Epub 2022 Nov 9. PMID: 36352500; PMCID: PMC10006627

- Mengesha, M.B., Chekole, T.T. & Hidru, H.D. Uptake and barriers to cervical cancer screening among human immunodeficiency virus-positive women in Sub Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Women’s Health 23, 338 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02479-w

- Santesso N, Mustafa RA, Schünemann HJ, Arbyn M, Blumenthal PD, Cain J, Chirenje M, Denny L, De Vuyst H, Eckert LO, Forhan SE, Franco EL, Gage JC, Garcia F, Herrero R, Jeronimo J, Lu ER, Luciani S, Quek SC, Sankaranarayanan R, Tsu V, Broutet N; Guideline Support Group. World Health Organization Guidelines for treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2-3 and screen-and-treat strategies to prevent cervical cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016 Mar;132(3):252-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.07.038. Epub 2015 Dec 14 PMID: 26868062.

- Black, E., Hyslop, F. & Richmond, R. Barriers and facilitators to uptake of cervical cancer screening among women in Uganda: a systematic review. BMC Women’s Health 19, 108 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0809-z

- Solomon K, Tamire M, Kaba M. Predictors of cervical cancer screening practice among HIV positive women attending adult anti-retroviral treatment clinics in Bishoftu town, Ethiopia: the application of a health belief model. BMC Cancer. 2019 Oct 23;19(1):989. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6171-6 PMID: 31646975; PMCID: PMC6813043

Fig.1. The uptake of the organized screening in 2015-2021 [8].

Fig.2. The proportion of CC and the precancerous conditions revealed by the screening measures out of the total number [8]

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | Total numberN (%) | Barriers | P- value | ||

| Psychological,N (%) | Knowledge related,N (%) | Doctors and Facility related, N (%) | |||

| Total number | 482 | 157(32.57) | 164(34.02) | 161(33.40) | |

| AgeDf=4, χ2 value=0.0175 | .999 | ||||

| 30-39 | 183 (37.97) | 60(32.79) | 62(33.88) | 61(33.33) | |

| 40-49 | 159 (32.99) | 52(32.70) | 54(33.96) | 53(33.33) | |

| 50-60 | 140 (29.05) | 45(32.14) | 48(34.29) | 47(33.57) | |

| Residence AreaDf=2, χ2 value= 7.59 | .023 | ||||

| Rural area | 294(61) | 82(27.89) | 106(36.05) | 106(36.05) | |

| Urban area | 188(39) | 75(39.89) | 58(30.85) | 55(29.26) | |

| EducationDf=6, χ2 value= 14.493 | .025 | ||||

| Secondary school | 31 (6.43) | 13(41.94) | 11(35.48) | 7(22.58) | |

| Secondary Special/Vocational | 169 (35.06) | 59(34.91) | 59(34.91) | 51(30.18) | |

| University diploma | 256(53.11) | 71(27.73) | 85(33.2) | 100(39.06) | |

| PhD | 26 (5.39) | 14(53.85) | 9(34.62) | 3(11.54) | |

| Marital StatusDf=6, χ2 value= 0.9081 | .988 | ||||

| Married or living together | 228(47.3) | 75(32.89) | 78(34.21) | 75(32.89) | |

| Single | 96(19.92) | 32(33.33) | 32(33.33) | 31(32.29) | |

| Divorced/separated | 92(19.09) | 30(32.61) | 32(34.78) | 30(32.61) | |

| Widowed | 66(13.69) | 20(30.3) | 21(31.82) | 25(37.88) | |

| ChildrenDf=2, χ2 value= 0.0145 | .992 | ||||

| Yes | 309(64.11) | 101(32.69) | 105(33.98) | 103(33.33) | |

| No | 173(35.89) | 56(32.37) | 59(34,1)8. | 58(33.53) | |

| Employment statusDf=4, χ2 value= 0.0924 | .998 | ||||

| Working | 244(50.62) | 80(32.79) | 82(33.61) | 82(33.61) | |

| Non-working at the moment | 196(40.66) | 64(32.65) | 67(34.18) | 65(33.16) | |

| Student | 42(8.71) | 13(30.95) | 15(35.71) | 14(33.33) | |

| InsuranceDf=2, χ2 value= 7.525 | .023 | ||||

| Yes | 189(39.21) | 51(26.98) | 62(32.80) | 76(40.21) | |

| No | 293(60.79) | 106(36.17) | 102(34.81) | 85(29.01) | |

| Health Status (by self-estimation)Df=4, χ2 value= 0.086 | .99 | ||||

| Excellent | 131(27.18) | 42(32.06) | 45(34.35) | 44(33.59) | |

| Good | 243(50.41) | 80(32.92) | 83(34.16) | 80(32.92) | |

| Poor | 108(22.41) | 35(32.41) | 36(33.33) | 37(34.26) | |

| Family history of Cervical CrDf=4, χ2 value=13.604 | .00867 | ||||

| Yes | 179(37.14) | 61(34.08) | 47(26.26) | 71(39.66) | |

| No | 173(35.89) | 57(32.95) | 58(33.53) | 58(33.53) | |

| Don’t know | 130(26.97) | 39(30) | 59(45.38) | 32(24.62) | |

Fig. 3. Demographic characteristics of the study population by barriers to Screening.

SUPPLEMENT 1

| N | Indicators(n=9) |

| 1. | Age |

| 30-39 | |

| 40-49 | |

| 50-60 | |

| 2. | Education |

| Secondary school | |

| Secondary Special/Vocational | |

| University diploma | |

| PhD | |

| 3. | Municipality |

| Urban | |

| Rural | |

| 4. | Marital status |

| Married or living together | |

| Single | |

| Divorced/separated | |

| Widowed | |

| 5. | Children |

| Yes | |

| No | |

| 6. | Employment Status |

| Working | |

| Non-working at the moment | |

| Student | |

| 7. | Insurance |

| Yes | |

| No | |

| 8. | Health Status (by self-estimation) |

| Excellent | |

| Good | |

| Poor | |

| 9. | Family history of Cervical Cr |

| Yes | |

| No | |

| Don’t know |

SUPPLEMENT 2

| N | BARRIERS REVEALING QUESTIONS(n=33) |

| KNOWLEDGE RELATED BARRIERS REVEALING QUESTIONS | |

| 1. | Do you know that prevention Cervical cancer is possible ? |

| 2. | Do you know that early detection improves the chance of curability and survival? |

| 3. | Do you know that cervical cancer can be prevented by cervical cancer screening as soon as it reveals pre-cancer conditions (and earyl stages of CC) ? |

| 4. | Do you know that the procedure of Pap-test is painless (hardly feelable)? |

| 5. | Do you know that the screening Pap testing can be passed in your local facility ? |

| 6. | Do you know that the screening visit takes about 15 min including registration procedure? |

| 7. | Do you know that the age frame of Screening programm includes 30-60 years old females? |

| 8. | Do you know that tap testing is not only required for the women who have sexual life // multiple sexual partners ? |

| 9. | Do you know that screening is not only required for the women who have complaints? |

| 10. | Do you know that pap test is not only necessary for the women who have kids ? |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL BARRIERS REVEALING QUESTIONS | |

| 1 | Do you care about your genital health? |

| 2 | Do you generally care about your health? |

| 3 | Do you fear of affected social image ? |

| 4 | Do you fear if cancer is revealed, your partner may feel mistrust ? |

| 5 | Are you afraid that test will detect cancer you and your family members may get in trouble ? |

| 6 | Are you afraid of procedure being paiful ? |

| 7 | Are you afraid of facility and medical instruments? |

| 8 | Do you feel embarrassed with your doctor ? |

| 9 | Do you think that screening visit is complicated process which you can subconsciously avoid ? |

| 10 | I don’t belive I can have problem? |

| DOCTORS AND FACILITIES RELATED BARRIERS REVEALING QUESTIONS | |

| 1. | Do you trust municipal Health care system and medical staff in our country in terms of pereformance accuracy of the procedure? |

| 2. | Is your doctor personally acceptable for you? |

| 3. | Do you trust in terms of saving information? |

| 4. | Do you trust in terms of sterility and safety of the procedure? |